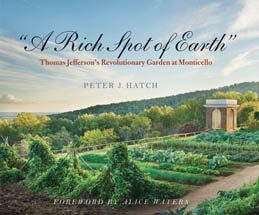

A rich spot of earth

One could argue the local foods movement in America has its roots in the red clay of the Piedmont, on a hilltop not unlike the Uwharries near Charlottesville, Va. Nearly two centuries before Alice Waters opened her landmark restaurant Chez Panisse in Berkeley, Calif., Thomas Jefferson understood the allure of applying French culinary techniques to local produce. Waters wrote the foreword of the recent book “A Rich Spot of Earth”: Thomas Jefferson’s Revolutionary Garden at Monticello. She describes Jefferson as “a personal hero” and calls on us “to reconnect ourselves to the pastoral and self-sufficient tradition” he built.

The book’s author, Peter Hatch, spent 35 years as the director of the gardens and grounds at Monticello. He contends the garden Jefferson created was “uniquely American in its scale, diversity, composition and experimental character.” Jefferson’s plans for this garden evolved over three decades, culminating in 1806 with a scaled drawing that called for a terraced, south-facing garden 1,000 feet long divided into nine beds. An adjacent area was dedicated to an orchard and vineyard, bringing the entire fruit and vegetable complex to seven acres.

The book’s author, Peter Hatch, spent 35 years as the director of the gardens and grounds at Monticello. He contends the garden Jefferson created was “uniquely American in its scale, diversity, composition and experimental character.” Jefferson’s plans for this garden evolved over three decades, culminating in 1806 with a scaled drawing that called for a terraced, south-facing garden 1,000 feet long divided into nine beds. An adjacent area was dedicated to an orchard and vineyard, bringing the entire fruit and vegetable complex to seven acres.

When Hatch arrived from Old Salem in 1977, people were beginning to realize “the gardens and landscape around a historic house deserve the same attention as the architecture and furnishings within.” In a less enlightened time, a portion of Jefferson’s garden had been paved to serve as a parking lot. Archeologists were brought in to survey the grounds and uncover the original footprint. Hatch researched heirloom varieties that appeared in the garden, drawing primarily on detailed historic accounts left by Jefferson himself. A product of the Enlightenment, Jefferson was a keen observer and an avid record-keeper. He started his garden diary, the Garden Book, at his boyhood home of Shadwell in 1766 and continued until Sept. 15, 1824, less than two years before his death. In one entry, he noted “how many lima beans would fill a quart jar.” This number wasn’t merely a factoid or curiosity – it informed how much garden space ought to be allocated to limas.

Even though Jefferson has been portrayed as a self-absorbed spendthrift – see David McCullough’s book John Adams – his ambitious garden wasn’t the folly of an idle gentleman. Granted, he once had a grand idea “to import Italian workmen who could also form an orchestra” – a scheme that never came to fruition – but his overall approach to the garden was rational and practical. It broke with the labor-intensive English kitchen-garden tradition which was still employed at many colonial estates, including Mount Vernon.

Jefferson had valid reasons for needing such a vast garden. In addition to feeding a large extended family, social norms of the day made it impossible to turn away the “streams of visitors” who came “to pay homage to the sage of Monticello.” His daughter once noted having more than 50 overnight guests. Jefferson was also committed to the experimental nature of his garden. He conducted trials in hopes of finding plants that would perform well in America. He valued self-sufficiency as a way to maintain our independence from Europe and to bolster the yeoman farmers he saw as the foundation of our society and democracy.

Many of his experiments failed. Hatch notes that few gardeners keep such detailed records of their failures. Jefferson was often left to purchase staples such as cucumbers, cabbage, potatoes, squash, melons, greens and hops from his slaves. They were allowed to work their own gardens and participate in a limited way in a market economy. Even though they could not experience Jefferson’s ideals of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, he perhaps allowed them their gardens because he believed “our country is built upon the principles of our farmers, and that our relationship to the land our food comes from is one of the most fundamental relationships of all.”

Jefferson filled his garden with his favorites and with novelties, with his desires and ambitions. Much has been made over Jefferson’s infatuation with English peas. In his writings, he mentioned at least 18 varieties by name – including Blue Prussian, Hotspur, Early Frame, Leadman’s Dwarf and Marrowfat – and he devoted a generous amount of the garden to them. He noted not only their harvest dates, but also “when they sprouted from the ground, the dates they blossomed, and the day on which the season’s first pod formed.” Jefferson was also a proponent of the tomato, a fruit still scorned by many Northern Europeans at the time. He was so impressed with sesame oil, he labored unsuccessfully for a dozen years to grow and extract it on a commercially viable scale in hopes of providing Americans with a locally produced alternative to Mediterranean olive oil.

In 1811, soon after Jefferson had retired to Monticello, he wrote, “I have often thought that if heaven had given me choice of my position and calling, it should have been on a rich spot of earth, well watered, and near a good market for the productions of the garden.” While he served as president, Jefferson dreamed of his garden at Monticello, but he never gardened in the nation’s capital. He did as many urban dwellers do today – he supported his local farmers market. He even created “a detailed chart delineating the first and last appearance of 37 vegetables in the local market between 1801 and 1809.”

Jefferson’s legacy has come full circle. Hatch has served as an adviser to First Lady Michelle Obama’s White House kitchen garden. In the spring of 2010 and 2011, he joined her – along with schoolchildren, chefs and other gardeners – in “a celebratory planting of Thomas Jefferson’s favorite vegetables.” We now have Tennis-ball and Brown Dutch lettuce, Prickly-seeded spinach and Green Globe artichokes growing on the South Lawn in honor of our nation’s “First Foodie.”

For more information about “A Rich Spot of Earth” and the historic gardens at Monticello, go to http://www.monticello.org/site/house-and-gardens/historic-gardens.