Shrinking Charlotte’s transit ambitions to get something built

Almost two years after Charlotte’s ambitious transit expansion plan was unveiled, local officials are admitting something that’s become increasingly apparent: It might not come to fruition, at least not as originally proposed.

That’s because the linchpin of the whole $13.5 billion Charlotte MOVES plan — a one-cent local sales tax that would require approval from the legislature in Raleigh and voters in Mecklenburg — is still stalled. There’s no hint of when Charlotte City Council might formally approach the N.C. General Assembly for permission to put a referendum on the ballot.

On top of that, a new Charlotte City Council was sworn in this week. Four of the members weren’t on council when the current plan was drawn up, and could well push for a new direction, especially given the lack of progress. Mayor Vi Lyles seemed to acknowledge as much last week in a talk at a meeting of the Charlotte Regional Business Alliance.

“In Charlotte, we have a plan and no money,” Lyles said, according to the Charlotte Business Journal. “I’m going to need your help to figure out how we can do this…It may not be what we proposed in the beginning, and I’m OK with that.”

There’s urgency now, Lyles said, to take advantage of some of the Biden administration’s infrastructure money before the opportunity passes by. So, what might a slimmed-down, reconfigured Charlotte transit plan look like? We decided to consult the Transit Time Forecast Machine (™) and present a few scenarios for how things could play out.

First, a refresher on how we got here. In late 2020, a task force appointed by Lyles presented recommendations for building out the city’s transportation infrastructure. The highlights should be familiar by now: an east-west Silver Line light rail; a revived Red Line commuter train to Mooresville; investment in the bus service, sidewalks, greenways and roads.

It’s a plan with something for everyone — transit riders, drivers, pedestrians and bicyclists — but the Silver Line is clearly the centerpiece. With a price tag of $8.1 billion (not even counting the hoped-for extensions to Gaston and Union counties), nothing else in the plan would cost nearly as much.

But without any money, arguments about the details (should the Silver Line go through uptown or around it?) have been mostly academic so far. After two years of talking and planning, we’re not much closer to actually building. Here are some other options:

Invest heavily in greenways, bike lanes and sidewalks. The $13.5 billion plan as it stands today would invest about 20% of the money in non-transit infrastructure, such as greenways, roads and sidewalks.

The city could ask for a smaller sales tax increase — perhaps just a quarter-cent. Most of that money could be spent on making the city one of the most bike and pedestrian friendly cities in the South, or even the nation.

- The Cross Charlotte Trail, running north-south from one end of the county to the other, has a price tag of around $112 million. Assume that two more similar-sized greenways could be created at a cost of $150 million each by linking up existing segments and building new trails, and you could have two more Cross Charlotte Trails for $300 million.

- A new protected bicycle lane through uptown cost about $7 million, and gives riders a safer route that’s fully separated from traffic by bollards and concrete dividers.

- The city of Charlotte has an estimated $1 billion-$2 billion worth of sidewalks that need to be built (based on almost 250 miles of identified sidewalk gaps and $4 million to $8 million per mile construction cost). Take the low end of that estimate and assume you can get developers to build a chunk as they redevelop areas, and you could make a big dent in our sidewalk gap for $500 million.

One benefit of building greenways, bike lanes and sidewalks is they cost little to maintain or operate. If the city decided not to seek a sales tax, it could turn to bonds to fund such a program.

A major bond issue is actually mentioned in Charlotte’s plan as a supplement to the proposed one-cent sales tax: “a significant one-time City of Charlotte Capital Investment Program (CIP) bond for mobility, supported through an increase in property tax and City voter bond approval.”

Would it be as transformative or ambitious as the current plan? Not by a long shot. Is it possible, and in a much quicker timeframe? Probably. Charlotte voters easily approved $197 million worth of capital bonds in 2020, and are expected to approve $226 million this year.

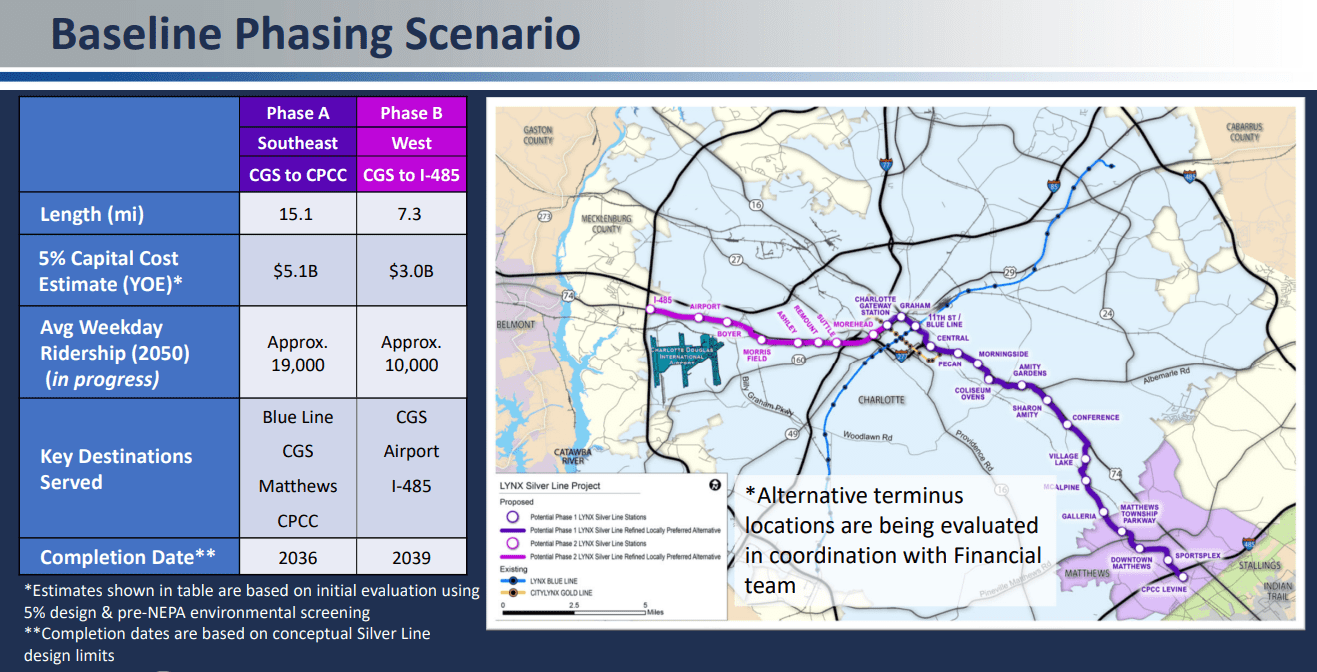

Shorten the Silver Line. Charlotte’s flagship light rail, the Blue Line, runs for 19 miles, from just north of Pineville to UNC Charlotte. The city wants an even more impressive east-west light rail: Running 22.4 miles from I-485 to Matthews, the Silver Line would connect Charlotte’s airport, center city and east side suburbs. Eventually, planners hope to extend the Silver Line to Gaston and Union counties, creating the first local cross-county rail line.

The 15.1-mile southeast section has been estimated to cost $5.1 billion (those estimates are likely to change, since CATS is studying bringing the Silver Line through, rather than around, uptown). The western section, only half as long, has a $3 billion estimated price tag.

Suppose Charlotte simply cut the Silver Line in half? The Blue Line was built in two sections, separated by a decade. And the city is already planning to build the Silver Line in segments, with the southeast section completed in 2036, three years before the western section. By modifying its plans to, say, build the first portion of the Silver Line from just the airport to uptown, or from the airport east across uptown to the Bojangles Coliseum, Charlotte might be able to cut the price tag in half, too.

A $4 billion project is expensive enough that it would still likely require a local sales tax of some kind (Transit Time has a good deep dive on why raising local property taxes enough to generate the same $225 million annually the one-cent sales tax is projected to raise is a nonstarter). But a project of that size could probably be supported by a smaller sales tax, such as a half-cent (which the legislature in Raleigh might be more willing to authorize).

And, following the 2019 voter rejection of an arts tax, Mecklenburg County still has the ability to ask voters to raise the sales tax a quarter-cent without going to the legislature. Combine a quarter-cent sales tax increase and a more modest property tax hike, and a shortened Silver Line might be possible without Charlotte relying on Raleigh for anything.

One potential sticking point: Without a clear path forward to making Norfolk Southern let the proposed Red Line use its tracks, voters in north Mecklenburg aren’t likely to support any sales tax referendum, even a quarter-cent. Any sales tax put on the ballot would need to ensure the northern towns benefit in some way.

Put more money into buses. Former council member Julie Eiselt was a big proponent of spending heavily on the bus system. She said it was a cheaper and more efficient way to move people around than light-rail.

But the city’s bus system has lost 75 percent of its passengers since ridership peaked in 2014. CATS operates numerous routes in outlying areas that are almost always empty. Will adding more service bring riders back?

Charlotte Area Transit System executives have previously said the bus system could be improved with substantially more frequent and reliable service would cost about $100 million to buy new buses and around $46 million a year in additional operating costs. That’s within the city’s capacity to fund through a bond issue or small sales tax increase.

Again, fixing the city’s bus system wouldn’t generate the same real estate development impact that a light rail project like the Blue Line creates. And it might not be enough to lure back riders post-covid. But buses have long been the backbone of Charlotte’s transit system, carrying the majority of riders, while receiving less investment than the light rail. It might be time to even the score.

Look through a regional lens and “Connect Beyond.” Charlotte’s transit plan has understandably hogged the spotlight. It’s big, bold, and, let’s face it, trains are just more exciting than buses. But there’s another plan out there: Connect Beyond. Led by the Centralina Regional Council in partnership with CATS, this bus-centric plan is focused on creating a regional transit system that could move people around not just Charlotte, but the 12-county surrounding area.

Connect Beyond doesn’t have a price tag attached to it yet. The plan envisions incremental steps, like synchronizing the bus schedules and payment options for CATS and the half-dozen smaller transit systems in the region. With half of Mecklenburg’s workers commuting in from outside the county (pre-covid, at least), the planners behind Connect Beyond say a regional approach is necessary.

Even though CATS has been a partner on Connect Beyond, a full-throated embrace of a regional bus system as the main transit initiative would be a major shift in focus. To be sure, Connect Beyond is the sort of plan that calls for more studies and more plans. There are a lot of question marks, including who would run a unified, regional bus system and who would pay for it. The recommendations call for studying “regional partnership structures” and figuring out how to pursue funding together as a region, rather than county-by-county.

That could open the door to creating a regional authority to run the transit system, something you’ll find in a lot of other large metro areas like Atlanta, Denver and Dallas-Fort Worth. And a regional authority could be able to pursue the kind of funding that might — eventually — allow the creation of a Silver Line that spans three counties.

So, is it possible that by focusing on the region for now, instead of Charlotte, the city could eventually get what it’s seeking — money to build its transit ambitions? Perhaps. In any case, one thing is becoming clear: The ideas in Charlotte MOVES need to find a new track to move forward.

This story was originally published on Transit Time, a joint newsletter produced by the Charlotte Ledger, WFAE and the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute.

Steve Harrison, WFAE