We live with ghosts of cities past

It’s that time of year again – when the ghosts of Christmas past, present, and yet to come arrive to haunt the old miser, Ebenezer Scrooge.

It is nearly impossible to extricate Charles Dickens’ works, including his beloved A Christmas Carol, from the city in which they are set: Victorian-era, dirty, industrial London. You can smell the soot-filled air while the desperate stares of the city’s poor haunt you on almost every page.

It’s not just in fiction where ghosts live on in cities. The way we experience cities is infused with the ghosts of what came before – like the lingering imprint of old text on an ancient palimpsest. Kevin Lynch’s urban design classic, The Image of the City, illustrates how we form vivid mental images of our surroundings in what he calls environmental maps. “Every citizen has had long associations with some part of his city,” Lynch writes, “and his image is soaked in memories and meanings.”

Lynch’s 1960 study takes place in three American cities (Boston, Jersey City and Los Angeles) and includes interviews with their residents. He introduces the idea of the legibility of cities – how we “read” them by constructing mental maps. A common theme he found was how the physical nature of the city symbolizes the passage of time.

Lynch’s 1960 study takes place in three American cities (Boston, Jersey City and Los Angeles) and includes interviews with their residents. He introduces the idea of the legibility of cities – how we “read” them by constructing mental maps. A common theme he found was how the physical nature of the city symbolizes the passage of time.

We can all probably relate to this scenario: You stop a stranger and say, “I’m new in town. Can you tell me how to get to (fill in the blank)?” He or she says, “Sure. Go down about three blocks and turn right on Main Street. There used to be a (something that isn’t there anymore) at the corner, but now it’s (some new thing).” We’ve all either been the one getting, or giving, directions via some missing object that is clearly still there in the local person’s mental map of the city.

The absence of physical elements anchored to the past creates a fluid environment that Lynch calls exciting, yet disturbing. “Many descriptions of the scene by established residents, young or old, were accompanied by the ghosts of what used to be there. Changes, such as those wrought by the freeway system, have left scars on the mental image.”

Consider this remark from one of the interviewers: “There seems to be a bitterness or nostalgia among natives which could be resentment at the many changes, or just inability to reorient fast enough to keep up with them.” This type of observation was common among the people who interviewed residents of the three cities.

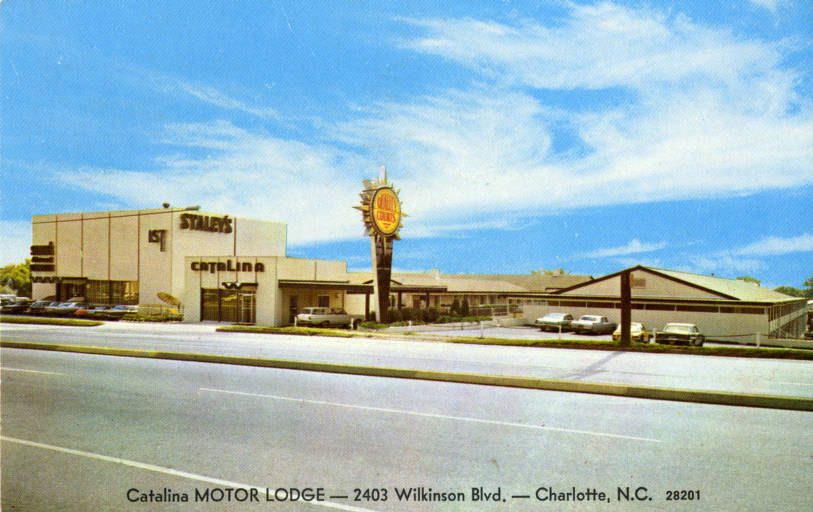

In Charlotte, we have our own ghosts. Tom Hanchett of the Levine Museum of the New South writes, on the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission website, “[t]he history of Charlotte’s Center City area is largely a story of what is no longer there.” Urban “renewal,” highways and similar construction and demolition projects cut deeply into our historic uptown and nearby neighborhoods.

For instance, I’ve heard stories of Thompson’s Bootery and Bloomery, which sat at Independence Boulevard before it was a freeway, and Pecan Avenue. It once sold Buster Brown shoes, but later added lingerie (interesting combination). It boasted a big display window at that prime corner and, I’ve been told by reliable sources, once had live models. Or how about what lies beneath Lake Norman?

Ghosts of Charlotte Past abound in nearby textile mills and around the UNC Charlotte campus. My colleague, John Chesser, told me about his old haunt, Herlocker’s restaurant. “That’s what everyone called it (being run by the Herlocker family), but the name on the sign was ‘The Park Drive In.’ ”

It was on North Tryon Street, just south of the Mallard Creek Church Road intersection. Chesser recalls that Mrs. Herlocker was always behind the high bar as you walked in – cooking on the giant grill, front and center, or running the register.

“It offered curb service and indoor seating. A specialty, the Herlocker Burger, came on a tiny paper plate, with batter-dipped onion rings or hush puppies … or fries in their own paper tray. It had great barbeque. And my favorite,” says Chesser, “a slice of cherry pie, warmed on the grill – served with a perfect rectangle of vanilla ice cream on top.”

Today there’s a Cook Out chain on that spot.

That’s the nature of ghosts – they never rest. I used to live in Virginia near a civil war battlefield with a unique ghost: the site where Stonewall Jackson’s arm is buried. In my hometown of Niceville, Fla.,  (home of the Boggy Bayou Mullet Festival, and yes, Niceville really is a nice place), I can direct you to the Little League baseball field – now they call it Rarick Field – up Highway 85. It’s catty-corner to what used to be the Kmart, but now is the county’s consolidated school kitchen. Or the downtown Fort Walton Beach intersection that used to be marked by a big statue of a knight in long-rusted armor, now gone.

(home of the Boggy Bayou Mullet Festival, and yes, Niceville really is a nice place), I can direct you to the Little League baseball field – now they call it Rarick Field – up Highway 85. It’s catty-corner to what used to be the Kmart, but now is the county’s consolidated school kitchen. Or the downtown Fort Walton Beach intersection that used to be marked by a big statue of a knight in long-rusted armor, now gone.

I wonder what happened to Ol’ Rusty – and how will I ever find that intersection again?